The American Story in Menus

By Frank Whitman

I read recently that QR code menus were being phased out. That’s OK with me. They were a good try during the pandemic, but it turns out that (like me) most people like to hold and look over the menu. I like to check out the appetizers, look for a glass of wine to match, glance at the entrees and take a sneak peak at the desserts. With those QR codes, you can only navigate section by section on a tiny screen.

The current exhibit at the Grolier Club in New York shows how important menus have always been. “An American Story in Menus, 1841 to 1941” displays a century of menus highlighting trends as eateries, circumstances and tastes changed. Since the early days of dining out, a menu has been an introduction to the eating experience as well as a source of necessary and  tempting information. Each of the eleven beautifully mounted displays covers roughly a decade

tempting information. Each of the eleven beautifully mounted displays covers roughly a decade

The Grolier, founded in 1884, is America’s oldest and largest society for book and graphic arts collectors and enthusiasts. Its townhouse location on East 60th Street holds a private library of rare books and prints as well as a double-height exhibition space open to the library stacks above. The Club is one of those under-the-radar institutions that make New York the cultural capital of the world.

The menu from Parker’s Restaurant in Boston, a precursor to the famous Parker House Hotel, is one of the earliest, dated June 29, 1842. The prices, shown in increments of a sixteenth of a dollar, allow for the

use of foreign money due to the shortage of United States gold and silver coins in circulation.

The menu includes both Green Turtle and Mock Turtle soups, items that were popular for decades to come. Menu categories included Fish, Boiled, Roast, Entrees along with Broiled and Fried. The menu also claimed Game of All Kinds.

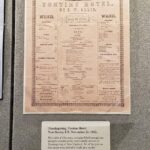

On November 25, 1852 The Tontine Hotel at the corner of Church and Court Streets in New Haven offered an extensive Thanksgiving Bill of Fare. Turkey was only one option among the choices that included pork chops, duck, eels, pigs feet and aspic of oysters. Marlborough Pie, a

popular apple-custard pastry, was a featured dessert. It was most likely made in the Amos Munson bakery just up the street, which baked 1000 pies a day for shipping to New York, where Connecticut pies were much prized.

The Menu for Lincoln’s Inaugural Ball in 1856 detailed the dishes on a 250 food long buffet table set up for 4000 guests. Lincoln ate with a small party before the horde rushed in at midnight.

As transportation and refrigeration improved, ingredients came from farther away and could be served cold. Barr’s Restaurant in Springfield, MA was offering 14 presentations of oysters and featured ice cream rooms in 1881. Like restaurants today, the menu advertised services for weddings and other occasions.

Beverages on early menus included lots of fortified wines: port, madeira and sherry. France supplied Champagne, Claret (Bordeaux), and sweet Sauternes. Hock (Riesling) from Germany was also popular.

The Sanitarium at Battle Creek was a health resort promoting a vegetarian and dairy-based diet. The menu focused on vegetables, grains, breads, and liquid foods. Superintendent Dr. John Harvey Kellogg went on to found the Kellogg breakfast cereal empire.

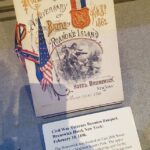

The prosperity of the Gilded Age and Victorian Era was reflected in creative and colorful menu design. The Gridiron Club dinner menu of 1897 was in the form of playing cards in a royal flush. Civil War veterans in 1896 had a colorful menu bound by a tricolor ribbon celebrating the Battle of Roanoke  Island.

Island.

Marsha and I were delighted to see a 1905 menu from Luchow’s in New York. We enjoyed eating in the venerable 14th street location many years later when we were dating.

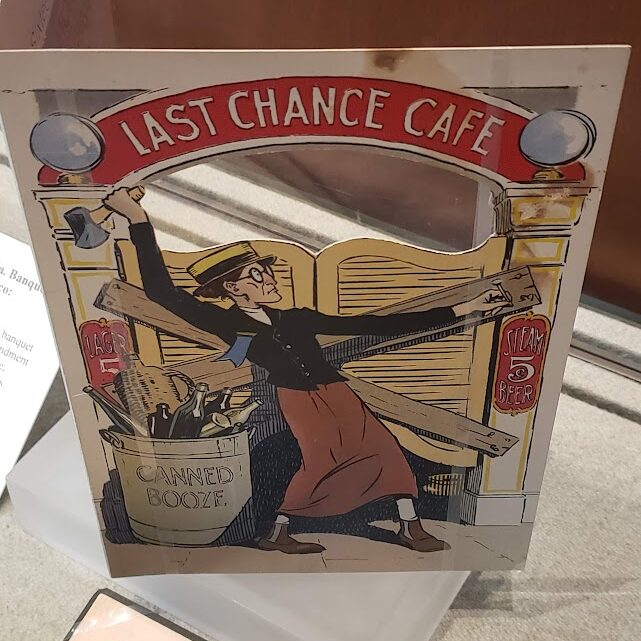

Menus were also an opportunity for political comment. The Canners League hosted by the American Can Company vividly protested the start of prohibition on their menu cover.

From beginning to end, the menus in the show are staggeringly long. A full page of fine print on the

menu from the St. Germain restaurant lists well over a hundred offerings and then states at the bottom, “For other dishes, see the al la carte menu.” I can’t imagine the size of the kitchen and brigade of cooks required to pull this off. It’s a far cry from today’s offerings of small plates, sharing plates, and large plates.

These menus survived because someone thought they were special. Saved as keepsakes, most did not make it beyond those memories – discarded by subsequent generations. That makes these both rare and exceptional examples of their kind that tell a wonderful story.

The free Grolier Club exhibit is open until July 29. It makes a good excuse to stroll Manhattan, delve into the culinary past, and then enjoy a good meal, which is exactly what we did.

No Comment