For most of my life, I wrinkled my nose at bread pudding. I just didn’t get it: the soft custardy (almost mushy) texture, simple flavors, and the rare appearance of chocolate didn’t put it on my list of desirable desserts. But with the passage of time, I have come to appreciate this most flexible, accommodating, and soothing dessert.

Making bread pudding is pretty straight forward: bake some bread that is past its prime in a custard. But, in fact, the possibilities are limitless. What type of bread? How rich a custard? And most importantly, what seasoning to use? This is where we get to customize the pudding to our own tastes and create the dessert of our dreams.

First the custard. The principal issue here is the ratio of eggs to milk. Other topics to consider are the eggs, the choice of milk or cream, and whether or not to scald the milk. I surveyed a bunch of recipes both in cookbooks and online and found a wide range of answers to these questions. Mark Bittman, the cooking mentor for the current generation, in his comprehensive book How to Cook Everything, uses one cup of whole milk to one large egg. Paula Deen, the well-known southern cook, in Kitchen Classics, recommends two eggs for each cup of milk. Thomas Keller, as might be expected from a world-renowned chef, has a rich ratio of five eggs to 2 ¼ cups. The Joy of Cooking, a standard text for many, and Alice Waters, the groundbreaking California chef, use egg yolks, not whole eggs. For my recipe, I’m sticking with Bittman — one whole large egg for one cup of milk.

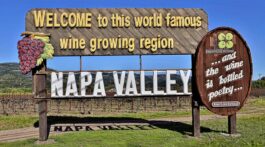

I say milk, but there is, of course, some diversity of opinion on what level of cream content your milk should have. Surprisingly, Alice Waters, known for fresh and light cuisine from local sources, specifies two cups of milk and two more of cream to go with her seven egg yolks — rich custard indeed. Paula Deen added a quarter cup of heavy cream to her three cups of milk – an amount so small as to seem insignificant. All the other sources recommended whole milk. I would have used whole milk but didn’t have any, so I mixed two cups of 1% with one cup of Half and Half to approximate whole milk.

There is also a question of scalding the milk – warming it to where there are small bubbles around the edge and a skin across the top. This seems to be anachronistic, dating back to when it was important to eliminate any bacteria remaining in the milk. It didn’t seem necessary, but rather than using cold milk right out of the frig, which would lengthen cooking time, I heated the milk in the microwave for a few minutes to bring it up a little over room temperature.

While we’re discussing the custard, the issue of sweetening comes up. Again there is a wide range of opinion, anywhere from a half cup to two cups of sugar for three cups of milk. Most sources called for white sugar, a couple used brown (light or dark) and one included honey. Again, I followed Bittman’s lead for a half cup but used dark brown sugar for added flavor.

The bread has a big impact on the final pudding. Some recipes call for a brioche or challah (eggy, buttery) bread, but having used those for french toast, they seemed a little soft to me. Some of my sources specify white bread measured by the slice, but again that seems too mushy and bland. Perhaps this is the source of my initial aversion to bread pudding. We had a round loaf of peasant-style bread on hand, firm with an even texture and a soft but hearty crust. I cut one-inch cubes, enough for four cups, lightly packed. Some diced sweet rolls or cinnamon rolls can be included in the four cups, if you have any. Remember, bread pudding is ultimately a way to use up old bread.

After the fundamentals of custard and bread, seasoning is the next area for consideration. Cinnamon is essential, all but one source included vanilla, and I, of course, have to have a few scrapes of fresh nutmeg for a Connecticut accent. Other flavorings can include lemon zest, almond extract, bananas, liquor, a pinch of salt or even chocolate. I kept it simple, although some dried cranberries and golden raisins were added for the traditional dried fruit component.

Cooking time and technique are the last items to think about. Half of the recipes called for a water bath — baking the pudding inside a second pan of water. This provides a more even and gentle heat to keep the custard tender. I’m sure it’s important for a plain baked custard, but with the bread soaking up the liquid, it didn’t seem crucial. As a lazy cook, I skipped the water bath and was very happy with the resulting consistency of my pudding. Baking time will vary, so test the custard by inserting a knife in the center. If it comes out clean, then it’s done. The pudding will puff up in the pan while cooking, so leave some extra room. It will settle down as it cools.

A quick word on method. After the custard is mixed, it’s important to let the bread soak until it’s fully saturated – 15 or 20 minutes, depending on the bread.

Bread Pudding is counted among the world’s most beloved comfort foods. Whether you’ve always craved it, or, like me, have come to it recently, I hope it makes your eyes light up and mouth water. For my recipe visit www.Franksfeast.com.

HARD CIDER UPDATE

Just before Christmas I did the second racking – moving the cider off its sediment. Fermentation has slowed to a barely perceptible bubbling. The cider was surprisingly clear, with about an inch of sediment in the carboy. This racking involves siphoning the cider from the carboy to the bucket, cleaning the carboy, then siphoning the cider back into the carboy and cleaning everything again. It turns out that once the fermentation is underway, cider making is mostly housekeeping!

No Comment